Email today to buy or store your DASEIN System 6 can carton today.

[email protected]

Will the UN Ever Function with Unpaid Volunteers?

It is highly unlikely for the United Nations (UN) to transition to a model where it operates solely with unpaid volunteers. The UN is a complex intergovernmental organization with a vast scope of operations, including peacekeeping missions, humanitarian aid, diplomacy, and global policy coordination, all of which require professional staff, specialized expertise, and significant funding. Here’s why a volunteer-based model is improbable:

- Operational Complexity: The UN employs over 37,000 staff across its agencies, funds, and programs (e.g., UNICEF, WHO, UNHCR). These roles demand technical skills, experience, and continuity that unpaid volunteers, who often lack the time or resources to commit long-term, cannot consistently provide.

- Funding Structure: The UN’s budget (e.g., $3.5 billion for the 2024-2025 regular budget, plus billions more for peacekeeping and agencies) relies on member state contributions. Salaries ensure accountability, professionalism, and the ability to attract qualified personnel. Volunteers, while valuable, cannot sustain the scale and consistency required.

- Historical Precedent: The UN has operated with paid staff since its founding in 1945. Volunteers, such as those in the UN Volunteers (UNV) program, supplement specific initiatives (e.g., 11,000 volunteers in 2023), but they are not a replacement for salaried employees. Shifting to an unpaid model would require a fundamental restructuring of its charter and operations, which member states are unlikely to support.

- Incentives and Corruption Concerns: Your mention of “salaries or kickbacks” suggests concerns about financial motivations or corruption. While inefficiencies or mismanagement exist in any large organization, salaries are standard for professional work. A volunteer model could introduce other issues, like reliance on external funding sources, which might increase influence from private entities or wealthy donors, potentially undermining impartiality.

Will the UN Continue to Grow Due to Salaries or Kickbacks?

The UN’s growth is driven by its mandate to address global challenges (e.g., climate change, conflict, poverty), not solely by salaries or alleged kickbacks. Its budget and staffing levels are determined by member states through bodies like the General Assembly and are subject to oversight. However, criticisms of bureaucracy, inefficiency, or misuse of funds persist, as noted in posts on X and various reports. For example, audits by the UN’s Office of Internal Oversight Services have occasionally flagged financial irregularities, but these are not the primary driver of the UN’s expansion. Growth is more tied to increasing global demands (e.g., refugee crises, pandemics) than personal financial incentives.

How Can the UN Be Dissolved?

Dissolving the UN would be extraordinarily difficult due to its entrenched legal, political, and diplomatic framework. Here are the key steps and challenges involved:

1. Charter Amendment or Termination:

- The UN Charter, signed in 1945, does not explicitly provide for dissolution. Article 108 allows amendments with approval from two-thirds of the General Assembly and ratification by two-thirds of member states, including all five permanent Security Council members (U.S., Russia, China, UK, France). Proposing dissolution would require unprecedented consensus.

- Even if a dissolution clause were introduced, any permanent Security Council member could veto it, as they hold veto power over substantive decisions. Major powers benefit from the UN’s platform, making their agreement unlikely.

2. Withdrawal of Member States:

- Member states could theoretically withdraw en masse, as no country is forced to remain (e.g., Indonesia temporarily withdrew in 1965 but rejoined). However, coordinated withdrawal by enough states to render the UN defunct is improbable, given its role in global stability and diplomacy.

- The U.S., which funds about 22% of the UN’s regular budget, could cripple operations by withdrawing funding, but this would face domestic and international opposition due to the UN’s role in advancing U.S. interests (e.g., sanctions, peacekeeping).

3. Practical Challenges:

- The UN’s dissolution would disrupt global systems like refugee aid, food programs (e.g., World Food Programme), and international law (e.g., International Court of Justice). No alternative framework exists to replace these functions, making dissolution politically unpalatable.

- Replacing the UN with a new body would require recreating similar structures, as seen in the transition from the League of Nations to the UN in 1945, which was driven by a world war and global consensus—conditions not present today.

4. Public and Political Will:

- Posts on X and web sources often criticize the UN for inefficiency, bias, or overreach (e.g., Agenda 2030 concerns). However, these sentiments, while vocal, lack the coordinated global support needed to dissolve an organization with 193 member states.

- A grassroots movement or coalition of states could push for dissolution, but it would face resistance from countries reliant on UN aid and those valuing its diplomatic role.

Alternative Approaches to Reform

Rather than dissolution, critics often advocate reforming the UN, such as:

- Streamlining bureaucracy to reduce costs.

- Limiting the scope of certain agencies to avoid overreach.

- Enhancing transparency to address corruption concerns.

Conclusion

The UN is unlikely to shift to unpaid volunteers due to its operational needs and structure. Dissolving it would require near-impossible consensus among member states, particularly the Security Council’s permanent members. While frustrations with the UN’s inefficiencies or agenda are valid, reform is a more feasible path than dissolution. If you’re seeking specific actions, focusing on national policies (e.g., reducing funding or influence) or supporting reform initiatives might align with your concerns. For further details, you could explore UN budget reports at un.org or discussions on X about UN reform.

Basashi is the term for horse sashimi. The overwhelming majority of sashimi is fish.

ANOTHER SHIPMENT 💔🐴 At 4:05 AM, another export flight of horses left the Winnipeg airport & is now en route to Japan for slaughter. With the windchill, it was -30°C, yet horses were left in crates on the tarmac for hours. Canada must END this now! #CdnPoli

📷 @mbanimalsave

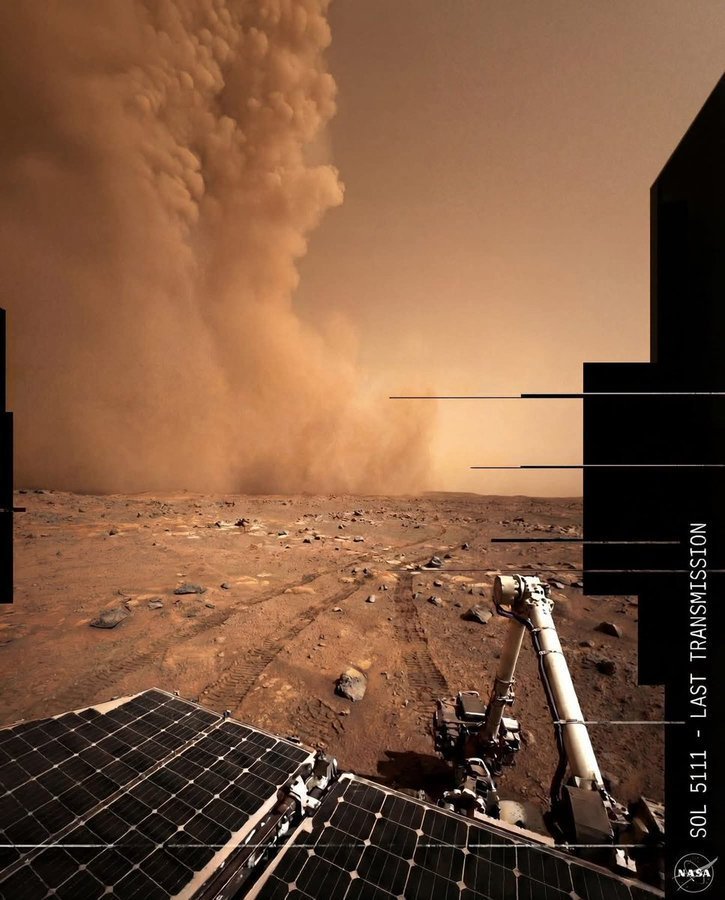

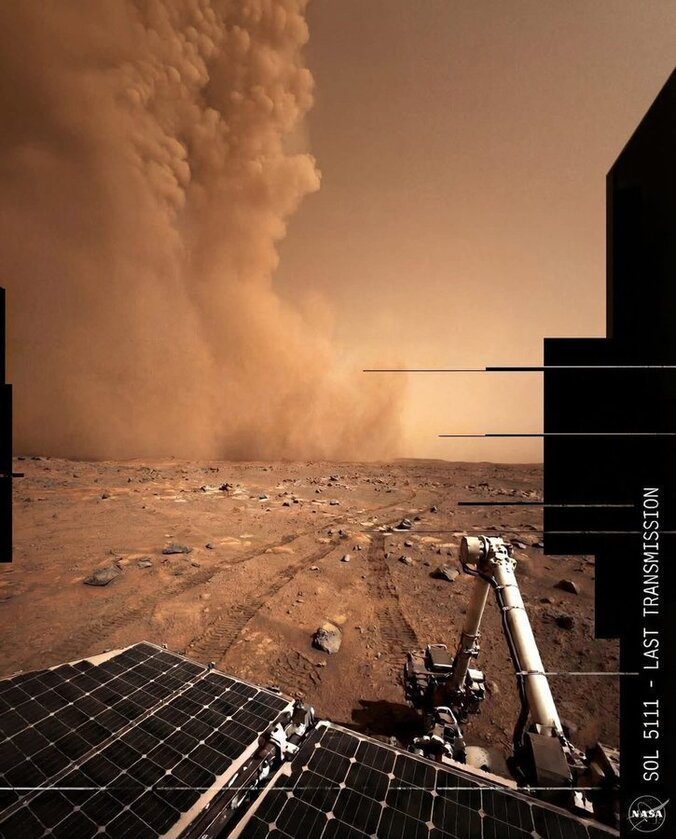

My battery is low and it's getting dark." These haunting words, sent from 225 million miles across the void, became the poignant farewell of NASA's Opportunity rover—affectionately known as Oppy—before it fell silent forever. Launched in 2003 and landing on Mars on January 25, 2004, Opportunity was designed for a modest 90-day (90-sol) mission to search for signs of ancient water. Instead, this plucky little solar-powered explorer defied every expectation, outlasting its warranty by a staggering factor of 55, roaming the Red Planet for nearly 15 Earth years (5,498 days / 5,352 sols). It traversed over 45 kilometers (28 miles), survived brutal dust storms, climbed crater rims, and delivered groundbreaking discoveries: definitive evidence of past liquid water, minerals formed in water, and hints that parts of ancient Mars could have supported microbial life.But in June 2018, a massive planet-encircling dust storm engulfed Mars, blocking sunlight for months and starving Oppy's solar ...

RFK Jr: Food is affecting everything that we do...if a foreign enemy or adversary did this to our country, poisoned us at mass scale, we'd consider it an act of war...

https://x.com/i/status/2023117209036312732